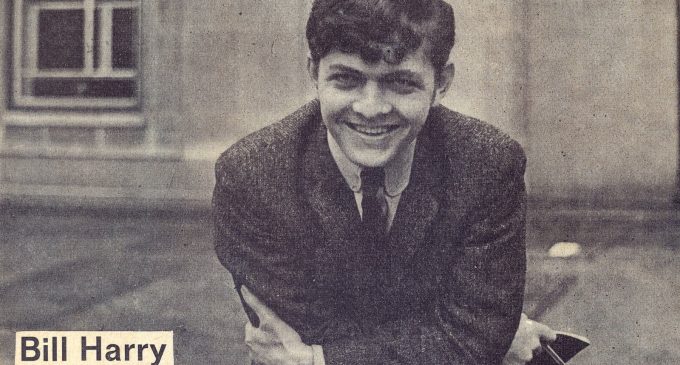

An interview with Bill Harry by Tsuf Plotkin

An interview with Bill Harry by Tsuf Plotkin.

- Brian claimed in his biography that he first heard about the Beatles when a young man came into the shop and asked for their single. is it true? And if not, why would he invent such a thing?

A: This isn’t true. On 6 June 1961 I entered NEMS, asked to see the manager and Brian came down. I showed him my copies of the very first issue of Mersey Beat and asked if he would take any copies. He did. He then phoned in the afternoon, amazed that they had sold out so quickly. The next batch also sold out, so Brian ordered 144 copies of issue No.2.

When Brian invited me into his office to talk, he had been fascinated by Mersey Beat because he never knew such a music scene existed on his own doorstep. Items in the first issue included John’s story of the formation of the Beatles and the entire back page was an advert for the Cavern, which was around the corner from his shop.

The full cover of Mersey Beat 2 featured a photo of the Beatles in Hamburg in their black leather and the headline ‘Beatles Sign Recording Contract,’ with the full story of their recording session. This was published on 20 July 1961. Paul McCartney, in his autobiography, states that this is how Brian discovered them. Brian invited me to lunch twice at the Basnett Bar in Basnett Street to ask me for as much information as I could tell him about the amazing scene I was reporting in Mersey Beat. He asked if he could be my record reviewer and I agreed. With issue 3 on August 3, 1961 his first record reviews appeared under his own name. And he also he took advertising. His advert appeared on the full page with Bob Wooler’s famous article about the Beatles, also in August. As the Beatles were the group I promoted most in Mersey Beat, Brian wanted more information from me about them and asked if I could arrange for him to visit the Cavern to see them, which I did.

Why didn’t he acknowledge this in his book, claiming he had never heard of them until a boy came into his shop on 28 October 1961 to order their record? This was over three months after I’d been discussing them with him. Perhaps it was because of what Philip Norman was to point out in his Beatles book decades later – that Brian didn’t like to attribute credit to anyone. Saying the boy came into his shop was a good opening to his book, but it is only relevant if he’d never heard of them before, which he already had.

The different between Brian’s story and what really happened is actually proven in black and white in the issues of Mersey Beat months prior to Brian’s claim.

I recall the quote from ‘The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance’, in which the newspaper editor says, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Q: What Made you Create the Mersey Beat.

A: I was a big science fiction fan and illustrated s-f fan magazines in Britain, Europe and America in my early teens. I created my own fanzine Biped and when I went to Junior Art School created a magazine called Premier. At Art College I created a magazine simply called Jazz and I also co-edited Pantosphinx for Liverpool University. I was also asked to create a magazine for Frank Hessy’s music shop called Frank Comments. I became associated with John, Stuart, Paul and George while at art college and helped book them for our college dances. Stuart and I proposed that we use union funds to buy a P.A. system which they could use. Virginia gave up her job to work with me on creating Mersey Beat and we borrowed £50 and I was able to not take any money as salary as I’d received a Senior City Art Scholarship and used the grant to help me to keep on publishing.

I used to work around the clock, particularly in the early hours of the morning when I would often go to the Pier Head to buy a cup of tea and a pie. A couple of times I collapsed in the office and had to be taken to hospital. As we neared the planned publication date I had to think of a title for the newspaper. I began to work out the area I’d be covering and visualized the entire Merseyside conurbation. Into the image came the vision of the policeman on his beat. This would be my beat, hence I came up with the name Mersey Beat. I must admit that working the number of hours I did, sometimes I’d get memory blocks. When I was writing about my friend Cilla, who sang occasionally with the Hurricanes, the Dominoes and the Big Three, my mind went blank when I went to write her surname. I knew it was a colour but couldn’t remember which. I picked up the piece about fashion which she’d written for me and it referred to colours of clothing, my eyes homed in on ‘black’ and I wrote ‘Cilla Black is a Liverpool girl who is starting on the road to fame.’ Of course, I should have written Cilla White, which was her real name, but she came into the office and told me she preferred it, even though her Dad didn’t like it.

Q: How Did the Beatles Really Sound in Those Days?

A: They were finding their feet, learning and experimenting and they’d already been around for two years when they became what I regarded as the college band, playing on the college dances on a bill with the Merseysippi jazz Band. It wasn’t until they went to Germany that they experienced, what I call, ‘a baptism of fire,’ which really forged them.

Q: Could Stuart play the Bass Guitar?

A: Of course he could. He was musically aware. He’d had many piano lessons, years previously his father had bought him a Spanish guitar. The rumours saying he couldn’t play all came from Allan Williams’ book, which was really written by Daily Mirror journalist Bill Marshall. They used one of a series of images of Stuart while tuning up for a rehearsal at the Wyvern Club and claimed he played with his back to the audience. The other photos from the same audition, unpublished at the time, show him playing full face. Musicians I knew from Hamburg said Stuart could play and faced the audience. When Stuart stayed behind in Hamburg, George Harrison wrote to him asking him to come back and join the group. In a 1964 interview in Beat Instrumental, in which he was discussing guitars, Paul commented, “I believe that playing an ordinary guitar first and then transferring to bass has made me a better bass player because it loosened up my fingers. NOT that I’m suggesting that EVERY bass player should learn on ordinary guitar. Stuart Sutcliffe certainly didn’t, and he was a great bass man.” Klaus Voormann said, “He (Stu) was a really good bass player, a very basic bass player, completely different. So basic that you could say he was, at the time, my favourite bass player, but primitive. But of all the people or groups, and when we saw groups later, he was my favourite bass player.” These are the people who were actually there at the time, listening to Stuart, not people who had never even heard him, but made out in their books and articles that he couldn’t play mainly because they’d read Allan’s book.

Q: What Did You Think of Pete Best’s Skills as a Drummer?

A: Like I said, they all had their ‘baptism of fire’ in Hamburg and all of them became part of a dynamic unit. On their return to Liverpool in December 1960 they proved a sensation at Litherland Town Hall, particularly with Pete’s ‘atom beat’, his new style which gave the band a tremendous sound. It was copied by other drummers and Pete became the most popular Beatle in Liverpool. Cavern disc jockey Bob Wooler decided to do what no other person had ever done before, he put drummer Pete in the front of an audience with the three guitarists behind him – and the girls pulled him off the stage, so it wasn’t repeated. This didn’t happen with any of the other members. No one who heard him playing during the two years he was active with the Beatles, including the Beatles themselves, actually criticized his drumming. That was to come after they sacked him.

Q: What is Your Explanation for the Beatles Sacking Pete Best?

A: Any explanation apart from those by specifically involved people is speculation. There was the rumour that when Brian took Pete into his office to tell him he was sacked, the phone rang and it was Paul saying ‘Have you told him yet?’ Here again, it’s difficult to bring up something you cannot really confirm. Pete was so popular in Liverpool that girls used to sleep in his garden overnight just to be near him. The explanation you would like can’t really be answered because it is only supposition. Some people said that it was due to Pete being so popular. That he was the best-looking Beatle. Others that the members felt that Pete’s mother Mona interfered too much. The stories about his drumming not being up to scratch is wrong and arose because of misrepresentation of what George Martin said when they had their first Parlophone audition. Session drummers were common in London studios because A&R men preferred their knowledge of working in a studio. Hits by the Dave Clarke Five, Kinks, Herman’s Hermits and many other leading 60s groups had session drummers on the records. George Martin mentioned that he’d prefer a session drummer, which Parlophone generally used in the studios. He was surprised when they returned to record and Ringo was with them and Martin told Brian that he considered Pete to be an asset to them. Co-producers Ron Richard and Martin both were unhappy with Ringo’s recording and arranged another recording in which they placed Andy White as session drummer. So Parlophone hired a session drummer, not because of Pete, but because of Ringo. Martin also criticized Ringo’s drumming and I don’t think Ringo ever forgave him.

Q: Mersey Beat Played such an Important role Promoting the Beatles’ Career in those Early Days. Was it Because You Considered Them as a Really Good Band or Because You were Just Good Friends or Both?

A: We all became friends in 1958. I first got to know Stuart and was then impressed by John and became his friend and took him to Ye Cracke where I introduced him to Stuart and Rod. We were together so many times in those days and I was a regular visitor to Stuart’s flat in Percy Street, where he painted my portrait. When they were all in Gambier Terrace I visited them all the time, was there when Stuart and John decided on picking a new name, Virginia and I used to talk to John for so long that we missed her last bus home, so John put us both up in the bath. Their friendship was the main thing and I miss the many talks and times we had together. When I began Mersey Beat it was obvious who I was going to promote most and I encouraged John to keep up with his writing and he became a Mersey Beat columnist, while Paul provided me with photos and wrote to me about their adventures abroad.

Q: Can You Clarify Whether the Story About Cunard Yanks Bringing Rock ‘n’ Roll Records from Overseas to Liverpool is a Legend or was it True?

A: More a piece of exaggerated fiction, although there was a tenuous relationship. Cunard Yanks had no impact on the local music scene. They brought clothes, records, books and magazines and various things back from America, mainly New York, but the records could be Billy Eckstein or Frank Sinatra as much as rock ‘n’ roll records. Every one of the early Beatles rock repertoire based on records were ones released and available in the UK. British divisions of EMI and others issued such records and the groups used to go into stores such as NEMS and listen to the records in the booths, writing down the lyrics (often getting them mixed up, as John did). Even small labels such as Oriole were releasing the Tamla Motown singles and the biggest market was Liverpool. I promoted Motown in Mersey Beat and took Stevie Wonder’s ‘Fingertips’ to the Cavern to get Bob Wooler to play it. Ringo heard it and asked me for the record. I gave it to him, contacted Oriole and they sent Ringo their entire Motown catalogue.

Q: Can You Tell Us About the relationship of John and Paul? Did they ignore George and Ringo? I mean Musically, and as Friends?

A: This must have been in my mind subconsciously when I kept approaching George whenever we met for drinks in clubs and kept saying that all the songs were written by John and Paul, why weren’t the Beatles recording any of his songs. He told me he wasn’t confident of writing lyrics. I pointed out that the very first mention in print of a Beatle writing an original song was on the cover of Issue No. 2 of Mersey Beat when I wrote that an original Beatles number ‘Cry for A Shadow’ was written by George. An alternative title had been ‘Beatle Bop.’ Apparently, the Beatles asked Bert Kaempfert when they were doing their recordings with Tony Sheridan whether they could record one of their own numbers. Kaempfert listened and chose George’s number. This was an instrumental and I was told it was because Rory Storm had challenged George to write a number like the Shadows. Hence the title, I presume. Later I was told it had been credited to George and John, although I believe it was mainly George. I is interesting to note that the very first original number by the Beatles had been recorded at Philips Studio in Kensington, Liverpool when they were still the Quarrymen. It was ‘In Spite of All the Danger’ and was credited to George and Paul. I kept stressing to George at our meetings that he was the composer on the first original Beatles number. I even suggested that he should write a number with Ringo. At another meeting he said that he did take my advice and write a number with Ringo, which I then mentioned in Mersey Beat. Don’t know what happened to the song, though. Then, when I was with them at the ABC, Blackpool, George thanked me. I asked him why and he said that he was going out one night and reckoned that he’d bump into me and I’d be bothering him once again about songwriting. So the title ‘Don’t Bother Me’ came into his head and he wrote the song and recorded it and told me in Blackpool that he’d already received a cheque for more than £7,000 for it.

Initially John didn’t want George in the group. He thought he was too young and treated him like a kid. I think it took away a lot of his confidence and the rejection always remained with him. He even asked John to help him with some advice about a song, but John refused. That’s why George had so many original songs on his ‘All Things Must Pass’ triple album. He’d had to fight hard to get any songwriting credit with the Beatles. Eventually it was Allan Klein who gave him his first and only Beatles ‘A’ side on a single, ‘Something’, which Frank Sinatra said was the best love song of the twentieth century – unfortunately, Sinatra also credited the number to John and Paul and not George. At his September 1981 Carnegie Hall concert, the highlight of his show was said to be ‘Something’ and the newspaper review read, “Sinatra introduced the song, written and recorded by the Beatles, by saying, ‘In a sense this is a personal tribute to Mr. Lennon. Also Mr. McCartney.’ Ironically, John and Paul had once said that they would known when they had ‘arrived’ as songwriters, when Frank Sinatra recorded a Beatles song.”

George’s songs on ‘Abbey Road’ proved that he was an exceptional songwriter who had been kept down during the Beatles recording career. Ringo, of course, was the newcomer – and felt it in the early stage. His confidence returned when it became obvious that he was the most popular Beatle during their early American trips, with more tribute discs written about him than the other members put together. The American press also appreciated his wit in interviews.

Q: I read that you were the one to introduce John to Stuart. Can you tell us about this first meeting and the beginning of their relationship?

A: At the college I’d heard a buzz about an extremely talented newcomer, whose name was Stuart Sutcliffe. I have always been attracted to talent, so I made it my business to get to know him. He was always with his best friend Rod Murray, who he shared a flat with. We began to chat a lot and had many shared interests, becoming kindred spirits. I used to spend time with him in his Percy Street flat discussing poetry, what the future might hold for us and metaphysical subjects due to his interest in the mystic philosopher Soren Kierkegaard. I was sitting in the canteen one day and noticed the unusual sight of what appeared to be a teddy boy strolling past. Suddenly, in my head the flash bulb lit, a eureka moment. That boy was the rebel. I looked around and most of the students were wearing duffle coats and polo necked sweaters. They were the conformists, he was the one who stuck out. I then told myself I had to get to know him, just like I did with Stuart. The opportunity arose, and I introduced myself. At first he tried his trick of being smart, but I coped with that as I came from a pretty tough area. We became friends almost immediately and decided to go to Ye Crack, the art college watering hole. Stuart and Rod were already there and I introduced John to Stu and Rod and the four of us became a regular group going to clubs, pubs and coffee bars together. With us he was excited talking about various cultural pursuits – books, paintings, movies and so on. He had a couple of other friends Tony Carricker and Geoff Mohammed and they were a mischievous bunch always looking for a local adventure. In some ways it illustrated two sides to John’s character – the erudite John who’d join Stu, Rod and me around a table in a pub or coffee bar to discuss cultural tastes and the scallywag with Tony and Geoff, going around causing chaos!

Q: What Do You think is the Main Factor that Made the Beatles so successful?

A: Spreading their wings so successfully across the spectrum by becoming innovators of an entire lifestyle, a landscape of ideas and imagination from music, songwriting, fashion, humour, touring, recording at a time when the world was undergoing change, they helped to change it.

Q: Can You Tell Us about the Discussions You Had in the Dissenters? John, Stuart, Rod and I were always involved in chats in pubs, coffee bars, clubs or parties. A lot of the time we’d discuss art, movies and literature. John devoured books, he was an avid reader. He also liked the cinema and would sag off art school to go to the Palais de Luxe in Lime Street with his girlfriends. We also used to go to the Art library at the Walker Art Gallery to look at American works such as the Saturday Evening Post, Steinberg, the New Yorker and so on. I ran the college film society and booked Avant Garde films like ‘Le Sang D’Un Poete’ and ‘Orphee’. Stuart was impressed by the Polish film ‘Ashes and Diamonds’ and its star Zbigniew Cybulski and began to wear dark glasses like Cybulski. He was more influenced by Cybulski than James Dean.

We were aware of the San Francisco City Lights books, the French Olympia Press books, the Angry Young Men books and so on. My particular favourite was Colin Wilson’s ‘Outsider’ and I felt that John had an association with this book, feeling that the subjects of it were just like him.

We talked about how Liverpool was, in some ways treated as a second-rate city. The media always concentrated on featuring the slums and back alleys, the poverty – nothing about the beautiful places, the parks, the wonderful Georgian buildings, the creative people. We had writers, artists, poets, musicians of a high caliber in Liverpool, but they never got any publicity. The main cities which controlled the media were London and Manchester, so Liverpool was basically ignored by the media and what was happening there generally got ignored. The Beatles, the Mersey Beat newspaper, the Mersey poets changed all that. During our initial meeting when I came up with the name ‘Dissenters’ – we were dissenting against the fact that Liverpool talent, which we believed was as good as anywhere, was ignored, so we vowed to use our own efforts to change it. John with his music, Stu and Rod with their painting, and me with my writing.

Just consider the implications. Four young students sitting in a pub in mid-1960 make a vow to make their city famous. Within just a few years what the Dissenters vowed, happened. John and his group created an international sensation, Mersey Beat became the most imitated publication in such a short time (24 other publications based on it) and suddenly Liverpool was acknowledged as the cultural hive we vowed it to become. I was sitting with poet Alan Ginsberg having a chat in Liverpool’s Blue Angel club. The world-famous poet was to declare that Liverpool “is at the present moment, the centre of consciousness of the human universe.” France’s great photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson was in Liverpool taking photos around the slums and broken buildings (the natural attraction for photographers and the rest of the media), Bob Dylan asked me to take him round the clubs to meet Liverpool poets, which I did – and the world’s media came to Liverpool!

Q: Back then did you think that the music that comes from Liverpool could be so famous all over the world?

A: Initially, no one did. But we were in a time of change and gradually it began to hit us that the Beatles and Liverpool were part of that change. Young people were beginning to earn money, have the freedom of choice, decide what music and fashion they could follow. See the scene in ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ with George and the businessman (Actor Kenneth Haigh, who is uncredited because he refused to have his name associated with the film. When it was successful he changed his mind. He passed away in February 2018) seeking to manipulate young people’s fashions. That’s why, in Liverpool, Mersey Beat became the young people’s voice.

Q: Could you tell what made the Beatles so different and outstanding, and made them that extraordinary band that they were? How different were the Beatles from other bands when they came back from Hamburg for the first time? Were they musically superior to other bands in Liverpool?

A: The transformation was electric. In Hamburg they were experiencing the long hours and the intense musical stage work which contrasted with the basic tight but relatively short appearances on Merseyside and were forging an act with extra dimensions. The other Liverpool act in Hamburg at the time was Howie Casey & the Seniors with their dynamic showman Derry Wilkie. Promoter Bruno Koschmeider used to egg on the Beatles that they should ‘Mach Shau’ like Derry. So they made a show – and what a show it was. Their major impact on their return was at Litherland Town Hall on December 27 which was the beginning of their gradual growth into legend. Also, in their black leather they stood out from other Mersey outfits, Pete Best had created the ‘atom beat’, John, Paul and George were performing musical skills and dynamism that had been forged during the months in Hamburg. They were now visually exciting, particularly to girls, but they also appealed to the male side of their audiences with their ability to produce music which made the hair on the back of your neck stand up! They could obviously be compared musically to the other lead, bass, rhythm guitar and drum groups like the Searchers, but Kingsize Taylor & the Dominoes, Howie Casey &the Seniors, the Big Three and others were equally impressive but in a different way.

Q: Did they really become a hit overnight after they came back from Hamburg (Mark Lewisohn tells that by January they became the biggest act in Liverpool?).

A: No. They were virtually unknown in Liverpool prior to Hamburg and when they arrived back in Liverpool in December 1960 they began their gradual rise to local fame. They appeared at the Casbah (the birthplace of the Beatles) for one gig and at Litherland Town Hall for one gig – which Bob Wooler talked Brian Kelly into giving it to them. They were a sensation at Litherland, but still literally unknown elsewhere. Stu was still in Germany and temporary bassist Chas. Newby refused to join them (apart from a couple of gigs). Becoming ‘a hit overnight’ took time, word of mouth slowly began to circulate. To help them out, Mona Best not only booked them for gigs at the Casbah Club, but did extra promotions for them at other venues. Most of the initial gigs came from Brian Kelly. He was so impressed with their debut at Litherland Town Hall that he gave them lots of work at his main venues. Some other gigs came from Dave Foreshaw and Sam Leach – but they were gradually making a name. The big turning point came at the end of February when Ray McFall began booking them for lunchtime sessions at the Cavern. This was a stroke of luck because a lot of members of groups were at work or in further education, but the Beatles had no other full-time work and were able to take up the offer. A few months later I launched Mersey Beat and promoted the Beatles so much that Bob Wooler said everyone was calling it the Mersey Beatle. Publishing the venues and the dates various groups were appearing on them also led to the fans travelling around Merseyside to support their favourites. But it was a process that led to the Mersey Beat poll at the end of the year. So, once again, you couldn’t say they were an overnight hit when they returned from Germany literally a week or two after they arrived back from Hamburg.

Q: Mark Lewisohn also wrote that when Brian started to manage them, they were considered a band that is very hard to work with and had a bad reputation – always late, bad attitude – is it correct? Didn’t they feel they lost fans and gigs because of the way they behaved?

A: The Beatles were a very close part of the lives of Virginia and I in those days as we were in touch virtually every day. They used to come to the office regularly to help out, Brian Epstein would also come to the office, bring Virginia a box of chocolate liqueurs, invite us to dinner on his birthday and we attended the majority of their Merseyside gigs. I wasn’t aware that they had a bad reputation and a bad attitude. The opposite in fact. We would all socialize with the other bands in pubs like the White Star and Grapes or at late night sessions at the Blue Angel Club or Joe’s Cafe and there seemed to be nothing wrong with their friendship with other groups or their promoters. Of course, Brian stopped them appearing at Brian Kelly’s venues because Kelly paid them with coins one night. Brian was also changing their image, putting them in mohair suits, getting them to bow on stage, stopping them from taking requests from fans, not to smoke on stage and so on. But as for the bad reputation, and loss of gigs and fans, it’s news to me and I was there.

Q: Was it something in Liverpool those days that gave them the motivation to succeed? What do you think made Liverpool special in terms of music in the late 50s? What was so special in the Liverpool bands that made them so successful over bands in other cities in the UK?

A: There was so many aspects to this which is why it is difficult to condense the many reasons in a relatively compact answer. For one thing, I doubt if many cities had so many places where young groups could play. There were more than 300 clubs which were part of The Merseyside Clubs Association (for social clubs, work clubs etc, which booked the local bands). There were so many other venues throughout Merseyside with groups in schools, church halls, ballrooms, cinemas, synagogues, clubs, stores, the cellars of houses with capacities which rose, such as the Tower Ballroom accommodating 5,000. Such a vast amount of venues was a factor. Then there were the numerous promoters – Charles McBain, Wally Hill, Brian Kelly, Sam Leach, Ray McFall, Jim Ireland etc, who kept the groups in regular work. Specifically, important were the city centre clubs the Cavern, the Iron Door, the Downbeat, the Marti Gras. In 1961, when Bob Wooler and I made a list of groups we were aware of, I published a list of almost 300. Following further research there were over 800 groups. Also, Liverpool probably had the most extensive range of musicians and performing poets. The poets became the most important British poets of the decade, Liverpool was called ‘the Nashville of the North because it had the biggest Country scene in Europe, we had a brilliant black music scene with groups like the Chants, the biggest Christian music scene in the world, the most important folk music scene in the UK – with the Spinners becoming Britain’s No. 1 folk sensation…and then there were the groups themselves headed by the Beatles. Liverpool probably had the world’s first female rock ‘n’ roll band with the Liverbirds and solo singers such as Beryl Marsden and Cilla Black.

The history of Liverpool also mattered because it was one of the world’s most important ports at one time, the gateway to New York from Europe, the home of the Irish fleeing the potato famine, the largest number of Scots living in a city outside Scotland, a large Welsh population, a melting pot of fabulous genres of music since the days of the sea shanties. The cosmopolitan mix was certainly one of the most important aspects. Also, Liverpool had a long association with New York, so we seemed to incorporate more of the American culture than other cities. Liverpool should have been twinned with New York. This is just scratching the surface, because there was a quality about the city and, as someone remarked “There must have been something in the water in Liverpool in the Sixties.”

Q: What kind of relationship did you have with the Beatles as individuals?

In my mind I call Ringo ‘the resilient Ringo.’ He was the true working-class hero of the Beatles who fought against adversity. In a coma for months, spending so much time at hospitals with ill health that when he did go back to school he was called ‘Lazarus’. When he left school, the teachers had to sign a form saying he’d studied there, but they couldn’t even remember who he was. I enjoyed Ringo’s company in the Jacaranda, the Blue Angel – where he’d meet up with Pat Davis. He always made you feel at ease and had a great sense of humour, despite being born into poverty and brought up by his Mum alone after his father left. The Beatles became the Beatles when Ringo joined, he added an indefinable something, apart from his musical ability.

George was the Beatle who was most stretched. He was never happy at school, didn’t take to education, ended up in a nowhere job at Blackler’s store and would probably have had a modest life in Liverpool for decades, but for becoming part of the dynamic four, despite John’s initial reluctance to let him become a member. With the accent always on John and Paul, George developed his own friends, ranging from the Monty Python set, actor John Hurt, Eric Clapton and Ravi Shankar. I’d initially spent time in clubs with him, having a drink and encouraging him to write songs, as I’ve mentioned before. His seeming isolation outside the stage and recording studio to the other members, increased his desire to cultivate his own friends. Ravi’s influence increased his love for Indian music and the Eastern religions and beliefs, such as reincarnation. His Monty Python mates led to him supporting ‘The Life of Brian’ and launching Handmade Films. It seemed obvious in the latter stages of the group’s career that he wasn’t happy being part of the Beatles anymore.

I remember Paul standing on the steps of the Art College on Panto Day. This was a day when we all collected for charity. Paul and George were next to the Art College at Liverpool Institute, so I got to know them then because they were present at our college canteen, they rehearsed in the life rooms (Rod and I were practicing skiffle music in one corner, me on kazoo, while they were rehearsing in another), and they also appeared at our dances, so I got to know all of them early on. With Paul he was always polite and considerate and helped a lot with their promotion in Mersey Beat. Virginia and I were on our way to the Cavern when he called out our name from the queue and gave us the Astrid Kirchherr photo which he’d brought from Hamburg for us and I was able to use it on the cover of issue No.2, which Paul recalled led to Brian becoming interested in the Beatles. Paul also used to write to me when they were travelling abroad and his descriptions of their appearance at the Liverpool strip club, the trip he made to Paris with John and other stories indicated a sense of humour in his writing which reminded me of John’s. After all, Paul had read Stephen Leacock’s ‘Nonsense Novels’ just like John and I had, which was an influence on us all.

I was closest to John, right from the beginning. I mentioned that I seemed to gravitate to talented people. There was something about John which made me feel we were kindred spirits. Often the two of us would drink together on a small round table in Ye Cracke in the room with the fire, beneath the print of ‘the Death of Nelson’ from the painting in the Walker Art Gallery. I’d heard that John wrote poetry which he initially denied, but I persevered, and he showed me one of his pieces, a funny rustic tale in itself with a twist ending. I loved it. I realized that John seemed somewhat guarded about the things he created, as if unaware of the reaction to them. I felt he was reluctant to show this side of his talent as he was unsure whether there would be criticism. I began to encourage him in his writing and kept him informed of the efforts Virginia and I were making to launch Mersey Beat. Naturally, I encouraged him to write for me and commissioned him to write a piece about the Beatles for the first issue. He eventually handed me a couple of scraps of paper, untitled, which I featured. I could tell John was unsure of my reaction to it, but I loved it and immediately ordered him a coffee and toast with jam (toast cost 1d extra with jam). This led to him giving me a large stack of his works, virtually everything he’d written, telling me it was mine to do with as I wished. I knew it was because he’d been so thrilled to see his first printed feature in Mersey Beat, that I was likely to continue using his material – which I did, giving him a pseudonym ‘Beatcomber’, because I liked the humorous writing of Beachcomber in the Daily Express and felt that John was equally talented as a humorist. I was always dropping around to the Gambier Terrace flat he’d moved into with Stu, Rod and some other students. These include the night Stu and John were trying to think of a new name for the group, the night when Royston Ellis told us how to get the ‘spitball’ out of a Vick inhaler, the night when Virginia and I ended up sleeping in the bathtub and so on. Fantastic times and a memory of being a foot on the step to the future.

Q: What were your favourite Mersey bands other than the Beatles?

A: There were some exceptional bands in Liverpool in those days. When ‘Sweets for My Sweet’ came out John Lennon said it was the best record to come out of Liverpool. The Searchers were another fab four outfit and should have achieved higher success than they did. The Big Three were the Liverpool legends, with Johnny Gus the most popular bass guitarist and Johnny Hutch the best drummer. Colin Manley and Brian Griffiths were arguably the best of all Liverpool guitarists. Kingsize Taylor and the Dominoes were the best rock ‘n ‘roll band in Britain in the 60s (I received an album they made in Germany under the name the Shakers. When out clubbing with George, I took him back to the office and gave him the album). The Chants should have been a major hit group and it’s a shame they never achieved the heights they deserved. Of course, everyone believed that Rory Storm was the king of Liverpool. Howie Casey, Beryl Marsden, Derry Wilkie, Steve Aldo, Jimmy Campbell, so many exceptional people and groups. The odds were against them because Brian Epstein had a degree of control over what Liverpool groups A&R men signed up due to his success with the Beatles, plus the media – newspaper, radio, television – didn’t want to promote any other acts from Liverpool and talent became more universal over the country. It was a time when television and radio wouldn’t play records by Liverpool’s non-Epstein bands.

Q: Was John a nice man or was he a bit violent?

A: If you initially stood up to John at the beginning, you got on fine. He did tend to take advantage of people who he thought weren’t strong willed. He was also violent in certain situations, as you’re aware. Thelma, his first girlfriend at the college, dumped him when he hit her. He beat up Cavern disc jockey Bob Wooler at Paul’s 21st party when he was drunk. But there were relatively few fights and he ran away from a few of them. He definitely had an acerbic wit. As far as I was concerned, he was a good friend. We always got on and I never had any problems with him. He’d come to the office with Cynthia and ask us out for breakfast, we’d drink together in various places, local pubs, coffee bars, the Blue Angel club. It was the same in London when he’d take us from one club to another in his chauffeur driven car. His Aunt Mimi said she’d always remember me because I was the first person ever to call John a genius. And he was – and geniuses are not like the rest of us, they have complex personalities, they have to wrestle with their talent, they often feel alien to other people. Their complexities make them seem difficult to the others and they also feel different from others. Throughout his life he was seeking to expand his consciousness. First it was with booze, then with amphetamines, then with drugs, all seeking to contact that inner place where the visionary ideas lay.

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment