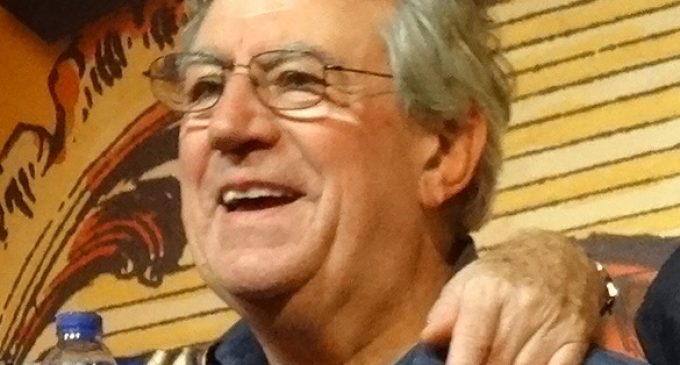

Terry Jones, charter member of Monty Python comedy team, dies at 77 – The Washington Post

Jan. 22, 2020 at 5:37 a.m. PSTIn 2016, his family announced he had a form of dementia that robbed him of speech. His agent confirmed the death in a statement.

The Welsh-born, Oxford-educated Mr. Jones spent a career embracing the erudite, the naughty and the gleefully idiotic. He directed movies, including three in the Monty Python franchise, became a scholar of the medieval era and wrote highly regarded children’s fiction. He also was a political essayist and author of opera librettos.

But it was his association with Monty Python — “Monty Python’s Flying Circus” — that established his cultural foothold.

The six-member troupe — the others were John Cleese, Michael Palin, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman and the impish American-born animator Terry Gilliam — debuted on BBC-TV in 1969 and had a spectacular five-year run in England. The show was exported to American public television in 1974 and was spun off into a film franchise and mini-industry of Python books and records.

There were lucrative onstage reunion shows, brimming with fans who mouthed all the lines. The phenomenon reached Broadway in 2005 with “Spamalot,” based on the 1975 movie “Monty Python and the Holy Grail,” a sendup of the Arthurian legends. “Spamalot,” directed by Mike Nichols and featuring a book by Idle, won a Tony Award for best musical and played four years in New York.

Python influenced many comedians, including Steve Martin, as well as the creators of the irreverent animated sitcoms “The Simpsons” and “South Park.” Junk email is called spam in homage to one of the group’s best-remembered sketches, featuring Mr. Jones as a waitress who recites a menu featuring an overload of the canned lunch meat in every item.

Python was often at its finest when at its most meaningless: a fish-slapping dance, a tradesman who sells dead parrots, a cross-dressing lumberjack who sings (Mr. Jones co-wrote the ditty, a burlesque of rugged manliness), and a civil servant who approves government grants for silly walks.

TV and pop culture scholar Robert Thompson credited the group with synthesizing the work of many absurdist comic forebears, including Spike Milligan, Ernie Kovacs and the anarchic “Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In.” By combining rapid-fire wordplay, historical japery, the subversion of middle-class mores and the flaying of upper-class twits, Monty Python “took silliness to renaissance levels,” Thompson said.

Mr. Jones brought a warped commitment to his characters. They included a naked organist, Karl Marx as a hapless quiz show contestant, a buffoonish cardinal in the Spanish Inquisition who helps to torture victims with soft cushions and the dreaded comfy chair, and a stuffy pubgoer who is subjected to befuddling sexual insinuations (“Nudge-nudge, snap-snap, grin-grin, wink-wink, say no more.”).

Often appearing in drag, Mr. Jones developed a specialty in portraying what he called “screechy middle-aged women.” One of his most prominent female roles came in the Python film “Life of Brian” (1979).

The Biblical romp and satire of religious fanaticism, directed by Mr. Jones and produced by former Beatle George Harrison, was about a young Jewish man (Chapman) who is born on the same day as, and in the stable next to, Jesus, and who is mistaken for the Messiah. Mr. Jones portrayed Brian’s mother, who is irritated that her son’s followers have massed at her doorstep. “He’s not the Messiah,” she snarls in a cockney accent. “He’s a very naughty boy.”

Religious groups picketed theaters, and film boards censored the movie — all but guaranteeing tremendous publicity and commercial success for a film that found in the sacred inspiration for the profane.

With Gilliam, Mr. Jones co-directed “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” and “The Meaning of Life” (1983). In the latter, an antic meditation on birth, death, sex, religion, class and the very concept of refinement, Mr. Jones played the obscenely gluttonous Mr. Creosote, who projectile vomits while devouring enormous amounts of fine food. He literally explodes after being offered one last indulgence — a wafer-thin mint — by an obsequious waiter (Cleese). “This is social satire of a very high order, not quite Swift, perhaps, but very fast indeed, and pungently and acidly observed,” Los Angeles Times reviewer Sheila Benson wrote.

Python historian Richard Topping noted that one of Mr. Jones’s principal creative legacies was behind the camera, keeping a watchful eye on editing and production values and providing the “comedic rhythm and visual logic that make much of the Python material so durable.”

He ensured, for example, that landscapes in a parody of westerns filmed in Britain evoked American vistas and not the rolling English countryside. It was a lesson he drew from his worship of a master of silent-era deadpan comedy.

“My big hero is Buster Keaton because he made comedy look beautiful,” Mr. Jones told David Morgan for the book “Monty Python Speaks!” “He didn’t say, ‘Oh it’s comedy, so we don’t need to bother about the way it looks.’ The way it looks is crucial, particularly because we were doing silly stuff. It has to have an integrity to it.”

An expert in the Middle Ages

Terence Graham Parry Jones was born in Colwyn Bay, Wales, on Feb. 1, 1942. The family soon moved to Claygate, near London, for his father’s banking job.

Mr. Jones was captain of his private school’s rugby team, but a long-gestating interest in poetry and acting led to his bond with Palin at the University of Oxford in the early 1960s. The duo created a sketch comedy troupe and over the next several years contributed to satirical TV programs such as “The Frost Report” and “Do Not Adjust Your Set.”

Cleese, Chapman and Idle — all Cambridge alums — and the expatriate Gilliam were also working in the light entertainment realm for British TV. Cleese and BBC producer Barry Took both claimed credit for organizing the writer-performers into “Monty Python’s Flying Circus” — a name chosen to evoke the moniker of a hinky theatrical booker and the shorthand for a World War I aerial squadron. The conjoining of those phrases meant nothing, but that was the point.

Competing ambitions eventually broke the team apart, although the group reunited intermittently. Cleese went on to co-create the British sitcom “Fawlty Towers” (1975-1979) and write and star in the film comedy “A Fish Called Wanda” (1988). Gilliam directed movies that included “Brazil” (1985) and “The Fisher King” (1991). Palin became a noted travel writer and documentary host. Idle continued acting and writing. Chapman died of cancer in 1989.

Mr. Jones’s directing career continued with an uneven parade of film credits as he immersed himself in a literary career. His accountant’s suggestion of investing in rare books sparked his interest in the Middle Ages. His volume “Chaucer’s Knight: The Portrait of a Medieval Mercenary” (1980), established his reputation for scholarship leavened by humorous turns of phrase. An Economist reviewer called Mr. Jones a “historian of impressive competence.”

Mr. Jones also wrote critically esteemed children’s books. His many volumes, including “The Saga of Erik the Viking” (the basis for one of his films), wove mature and even disquieting themes, including man’s propensity for violence, into inventive fables.

In 2005, Mr. Jones’s personal life drew tabloid scrutiny when he revealed that he and his wife of nearly 35 years, Alison Telfer, had an open marriage and that he was involved with Anne Soderstrom, a Swedish-born Oxford student whose interests included modern languages, belly dancing and Monty Python.

His marriage to Telfer ended in divorce. In addition to Soderstrom, whom he married in 2012, survivors include two children from his first marriage, Sally and Bill, and a daughter, Siri, from his second.

In 2009, Mr. Jones went on tour again with his surviving Python chums, in part, Cleese joked, because “anyone entering on fatherhood at age 67 needs all the help he can get.” Mr. Jones spoke to the New York Times that year about Python’s enduring appeal — and why, he joked, its success meant that it had fallen short of its anti-establishment aspirations.

“The one thing we all agreed on, our chief aim, was to be totally unpredictable and never to repeat ourselves,” he said. “We wanted to be unquantifiable. That ‘pythonesque’ is now an adjective in the O.E.D. means we failed utterly.”

Source: Terry Jones, charter member of Monty Python comedy team, dies at 77 – The Washington Post

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment